Go For Chance

As he does every afternoon, Mohammed, a 17-year-old Sudanese boy, takes the bus to the Eurotunnel area. "I go for chance" is the expression exiles use when they roam the parking lots, looking for a vehicle to cross the strait.

For nearly 20 years, people have been arriving in Calais, mainly from Africa and the Middle East, attempting to cross into England illegally. Often rejected for asylum, this is their last hope to start a new life. While the number of exiles in Calais has significantly decreased since the dismantling of the "large jungle" in 2016 (currently estimated between 800 and 1,500 people), city and state policies have become more repressive. To make their settlement as difficult as possible, camps are raided by law enforcement every 48 hours, then cleared and fenced off.

The lives of these exiles are shaped by visits from humanitarian organizations, evictions, and desperate attempts to reach England. For them, Calais is the last stop on a long journey that seems never to end.

Calais, March 2020 – November 2021 The names marked with * have been changed.

Mohamed, aged 17, is Sudanese. He had to flee Khartoum in December 2018. He arrived alone in Calais in February 2020, and every afternoon he wanders around the Euro-tunnel and the Cité Europe shopping centre in the hope of finding a car to reach England. He calls it "trying his luck". After a few weeks in Calais, Mohamed arrived in the UK and now lives in Brighton.

The camp for Eritrean exiles located in the industrial zone in Calais. Many of them have fled dictatorship and lifelong military service. In Calais, the Eritreans have organized themselves into two camps near a parking lot where trucks stop before heading to England, a strategic point for attempting to cross into that country.

A Sudanese exile's hands injured by barbed wire after trying to cross it.

"At night it is really cold, but we have no other choice. We have to stay awake all day and night to try to get to England," says Bilal, who lives with Alexander and other Sudanese under the railway station bridge in the centre of Calais.

The Iranian exile camp located in Rue des Huttes, in the Dunes industrial zone. This camp was dismantled in March 2020.

In Calais in winter, temperatures sometimes drop to -7 degrees. Sometimes, the prefecture of Pas-de-Calais implements the "Great Cold" plan by offering temporary accommodation to exiles. Adil, from Sudan, does not want to go there and prefers to sleep in his tent. "In the morning, we have to leave the shelter very early, there is a lot of noise and we can't sleep well. What we want is a long-term accommodation solution, not just when it is cold.

Alexander* a young Sudanese man in his tent, under the railway station bridge in the centre of Calais.

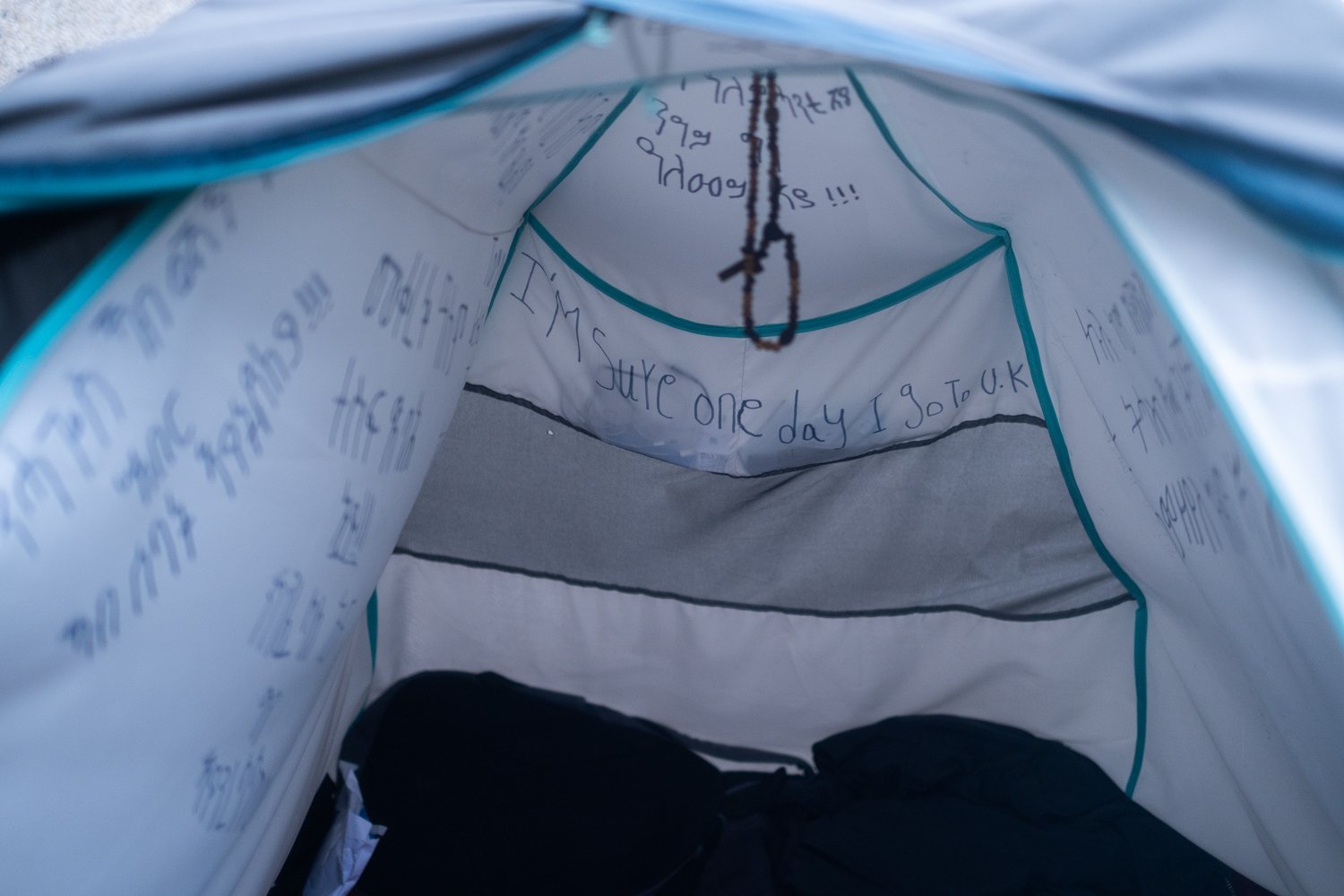

The tent of Issaï, an Eritrean exile in Calais for more than 6 months. In his tent, he writes proverbs in his mother tongue, Tigrinya: "Happiness is inside you, so don't try to find it in others" or "What is good in life is to think about the future, even when you are separated, you don't forget yourself" or "Tomorrow will be better than today".

As night falls, Apas, a young Sudanese, leaves the camp to try his luck near the Eurotunnel. He will spend the night here, on the edge of the motorway, trying to get into a truck. Apas managed to cross into England in early March 2021.

A group of young Sudanese are hiding behind a bank of the Transmarck. This is a highly supervised area with many car parks where trucks stop before going to England.

In a commercial area west of Calais, under the entrance of a former "Conforama" shop, a camp had been set up. It was evacuated after a few weeks.

Apas and Barid, both Sudanese, are resting in their tent after "trying their luck" all night. They are sleeping under the bridge of the train station in the centre of Calais.

Dismantling operations of the camps take place every 48 hours. According to the prefecture, these operations are set up "to put an end to illegal occupations. To avoid the constitution of unhealthy camps which would become shanty towns in a short time". The people living in the various camps must move their tents before the arrival of the forces of order, to avoid their seizure.

On 26 September 2020, at the initiative of some Calais citizens and supported by several associations, around 400 people (according to François Guennoc, a volunteer at the Auberge des Migrants) marched in the streets of Calais for "respect for the fundamental rights and dignity of exiled people" after the Pas-de-Calais prefecture banned food distributions in certain streets by associations not mandated by the State at the beginning of September.

"A human being is a person who dreams" says 26-year-old Noël, who comes from Conakry in Guinea. Noël applied for asylum in Germany but was rejected. « I was deported to Italy because I am ‘dublined' , no one wants to accept me here ». After spending more than 6 months in Calais, Noël managed to reach England on 14 July 2020.

A group of young Sudanese hide near the Eurotunnel to try to get into a truck. In October 2021, a 20-year-old Sudanese boy, Yasser, died, crushed by a lorry he was trying to smuggle in.

The group hides in the gutter next to the highway. They run and jump into the trucks that stop.

"Calais is really hard" says Issa as he walks around Calais looking for a vehicle to reach England.

Migrants try to stop passing trucks to hide inside. They try between two and three times a week in the middle of the night most of the time. They call this practice "Doughar". That evening, the group was spotted by the police before they managed to access the highway. The CRS intervened and used tear gas to disperse the group.

Robel goes back to camp. He won't be going to England tonight.